Haikyo hospitals are undoubtedly some of the most interesting urbex places to explore anywhere in the world. In Japan they range from the tiny and abandoned wooden medical shacks that pre-date World War II, to goliath graffitied monstrosities that exist only as gutted husks of their former selves. Today’s location didn’t disappoint. The Tuberculosis Sanatorium for Children proudly hides a rich local history and a plethora of fascinating medical artefacts within its walls, albeit being a relic of a much darker era plagued by disease. But the day was warm and the autumn sunshine seemed to breathe a temporary respite into the rotting concrete structure. So, eager to take a step back in time, haikyo buddy Florian and I took the trundling train out to the countryside location to investigate.

Into the Concrete Shell

Arriving at the site, we discovered a rather bland concrete building in stark contrast to the colourful blue sky behind. Not at all the image of a hospital, especially one of the type that played such an important role in postwar Japanese history. Much to my partner’s surprise, the hospital was also looking rather worse for wear. Not due to any sort of natural degradation mind; the hospital had clearly been subject to a generous helping of vandalism since his chance visit 3 years earlier. The boards had been ripped off the windows and doors swung easily on their hinges in the light breeze. Broken glass littered the floor in every direction.

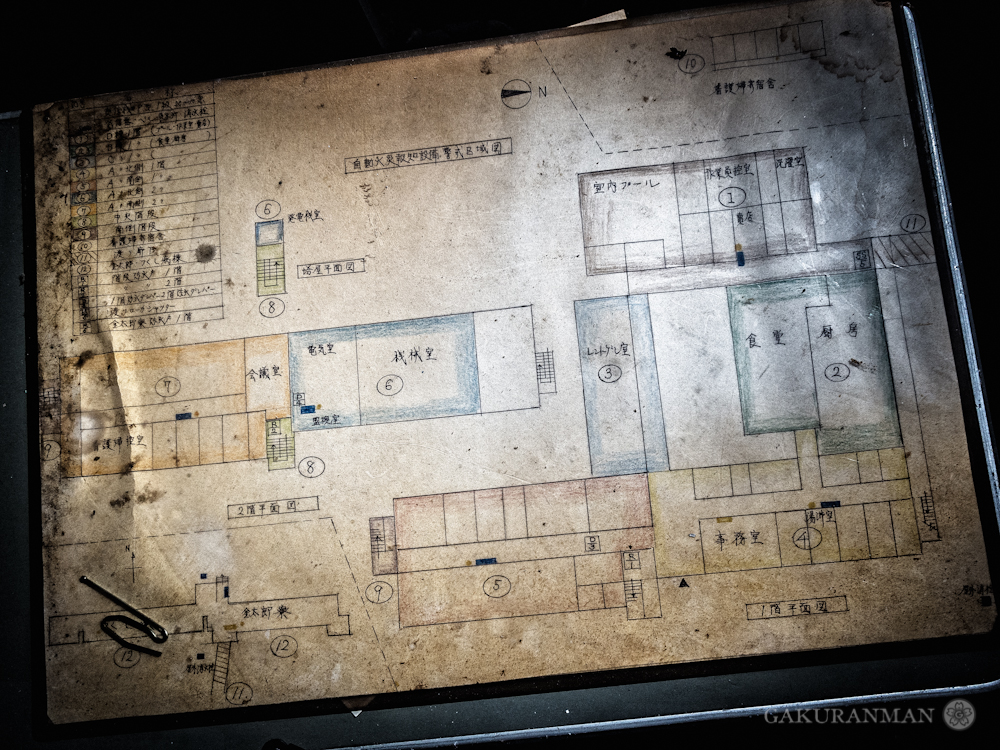

Exploring abandoned buildings has developed into something of a routine for me recently, and I suppose my friend could say the same. Once arrived, I prepared my camera and tripod, strapped a headlight on and filled my combat trouser pockets with a smattering of lenses to be used. With a curt nod, we set off in separate directions to explore the empty hospital hallways alone. Having the knowledge that a like-minded associate is just a stone’s throw away makes for reassuring exploration, but it wouldn’t be the same walking around shoulder to shoulder. A photographer needs freedom to capture his vision. Dark hallways need solitude to really be appreciated. There’s nothing quite like the excitement of being somewhere completely new, stumbling across long forgotten items while building up a mental map of the place. That is, if you can’t find the floor plans…

Storage closet. Check. Boiler room. Check. Toilet. Check. There was perhaps a time when I would dutifully photograph each and every nook and cranny in an abandoned location, but now I’m much more picky. It has to be an exceptionally good room for me to bother even snapping a picture. More often than not I find myself far more interested in photographing the small artefacts left behind and the way light creates interesting aesthetics in the darkness.

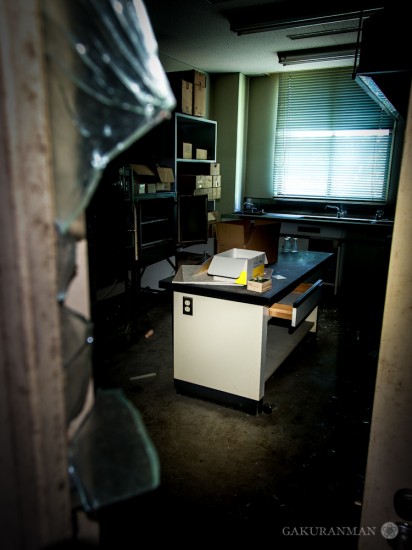

After a few bland and empty rooms, I finally find a consultation room. Although most of the windows are broken and letting light in throughout the hospital, some rooms are pitch black inside. The majority of my photographs are taken on a tripod using my headlamp to illuminate my surroundings over the course of a few seconds, so some pictures might be deceiving at times. The shot below is quite representative of how things actually look when I’m walking around in the darkness.

Next up, a laboratory. This is more like it! Boxes of glass beakers are pilled in dusty silence and old research apparatus calls out to my curious side. A lonely intravenous drip. A mysterious drum with heavy fitting metal lid. Huge oven-like metal closets. Just what were all these machines used for? Sterisliation of medical equipment was likely one use.

Here is a strange item. The handsome silver holder contained a white powder of sorts. I learned from Hirayuki the comments that this device is an environmentally friendly Peacock portable pocket warmer originally manufactured in 1923 and still made today by Hakukin. It works by platinum catalysis whereby vaporised benzine is turned into carbon dioxide and water, generating heat by the oxidisation process. The white powder inside is probably the residue of spent fuel.

Ah, and here we have that classic item seen strapped on the stereotypical doctor’s forehead – a head mirror. The reflective metal surface acts like a modern day ring light. Usually the disc will have a hole in the middle for the doctor to look through and a light positioned adjacent to the patient’s head, although they are rarely used today.

This next object just took my breath away. A medical box filled with supplies, such as triangular bandages, beakers, plasters, notebooks and even a large flag with the name of the hospital to be used in emergencies such as a natural disaster. I wonder how old the container is… It looks as though it could be from around the time of the end of the second world war, judging by the rustic design and aged look. Incredible.

Tuberculosis in Japan: A Short History

As fascinating as walking around the hospital was, something I didn’t quite appreciate until back home researching this article was the significance of tuberculosis itself. Tuberculosis is a potent disease that has had a devastating effect on many, many nations throughout history. The disease typically attacks the lungs (although it can infect any organ), spreading via air from person to person, with symptoms including a chronic cough, fever and weight loss (which is typically why the disease was said to be ‘consuming’ its victims). Although many infections are merely latent, active infections that are left untreated claim the lives of more than half the victims.

The disease itself spread wildly from the beginning of the 1800s in Europe and America due to the increase in urban crowding after the Industrial Revolution. The resulting epidemic finally calmed down somewhat in the early 1900s as living conditions improved. Similarly in Japan when industrialisation reached the country in 1895, a tuberculosis epidemic followed a very similar trajectory. However, the infection was not seriously brought under control until after World War II when effective antibiotic therapy arrived.

The terrible effects and high rate of mortality from tuberculosis during that time was such that it came to be known as the ‘Disease of a Ruined Nation’ (亡国病). It was untreatable, and being diagnosed with the disease was akin to being given a death sentence. As a result, many families denied infections in the household through fear of being ostracised from the community. With no alternative, people continued to work until they simply passed away, thus spreading the disease further in the crowded factory environments. It was only in the 1940s after the government realised that the epidemic was weakening the Japanese army did it show any interest in trying to quell the spread. A private organisation, the Japan Anti-Tuberculosis League, was left with the task of educating the public and stopping the panic. With the arrival of streptomycin in 1948, physicians no longer hid diagnosis and for the first time it was accepted that the disease had an infectious nature. The government finally saw to it that treatment was provided free for all patients and, with additional highly effective drugs, the epidemic of half a century was brought under control.

(New England Journal of Medicine)

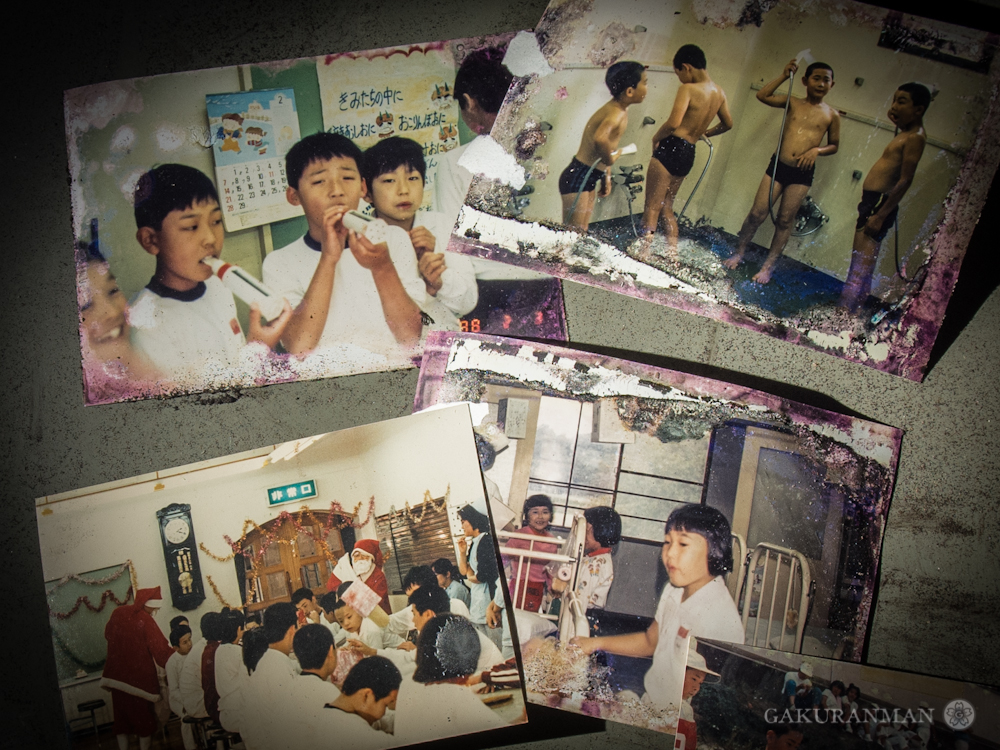

Sanatorium for Children

So where does the haikyo hospital fit into all this? Well, the sanatorium was originally opened in 1943, coinciding perfectly with the government’s increased efforts to bring tuberculosis under control in the early 1940s. It was to be a place for treatment and recovery for children who were suffering from tuberculosis and, later on, respiratory diseases such as bronchial asthma. The hospital’s history is also closely intertwined with a local school. In 1948 an annex was added to the existing hospital in order to allow children suffering from tuberculosis to continuing studying while on the road to recovery. This seems likely to be due to the introduction of streptomycin in the same year, which was the first antibiotic treatment for tuberculosis. In 1951 the school gained independence, moving to a nearby separate facility, and in 1958 changed its name, but continued to function as a special needs school for recovering children of elementary and middle school age.

However, the school’s fate was as intertwined with the original hospital just as much as its birth had been. The hospital finally closed its doors in 1992 due to the decline in the number of patients admitted, owing to lower numbers of children suffering from tuberculosis and the advancement of treatments for asthma. Despite some protests from staff and parents, the government finally closed the nearby school in March 2009 due to financial pressures and the diversification of education and medical treatment. A sad fate indeed for these two institutions and the staff employed there.

But why the need for a school so closely linked to a sanatorium? We find the answer in the treatment of tuberculosis. It turns out that it is a drawn-out and difficult process. Diagnosis is usually done by a chest x-ray and microscopic examination and, following that, treatment that relies on multiple antibiotics administered over an extended period of time. This is why the presence of a sanatorium such as this one and the efforts of the staff employed there were so important. The children needed support in their education, as well as a safe and secure environment while their weakened immune system recovered. Such was the live-in nature of the hospital that, in addition to the annexed school and dormitory, there were also facilities such as a large cafeteria and swimming pool for the children to use.

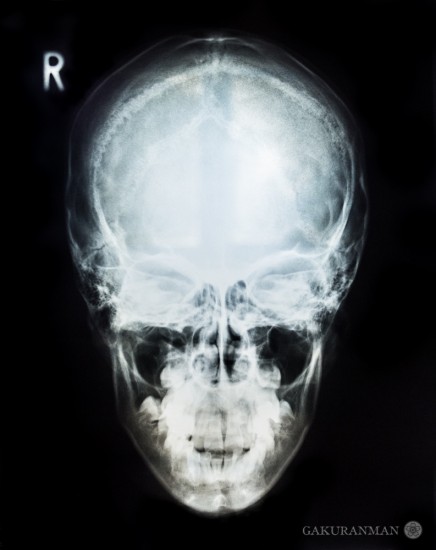

Radiology

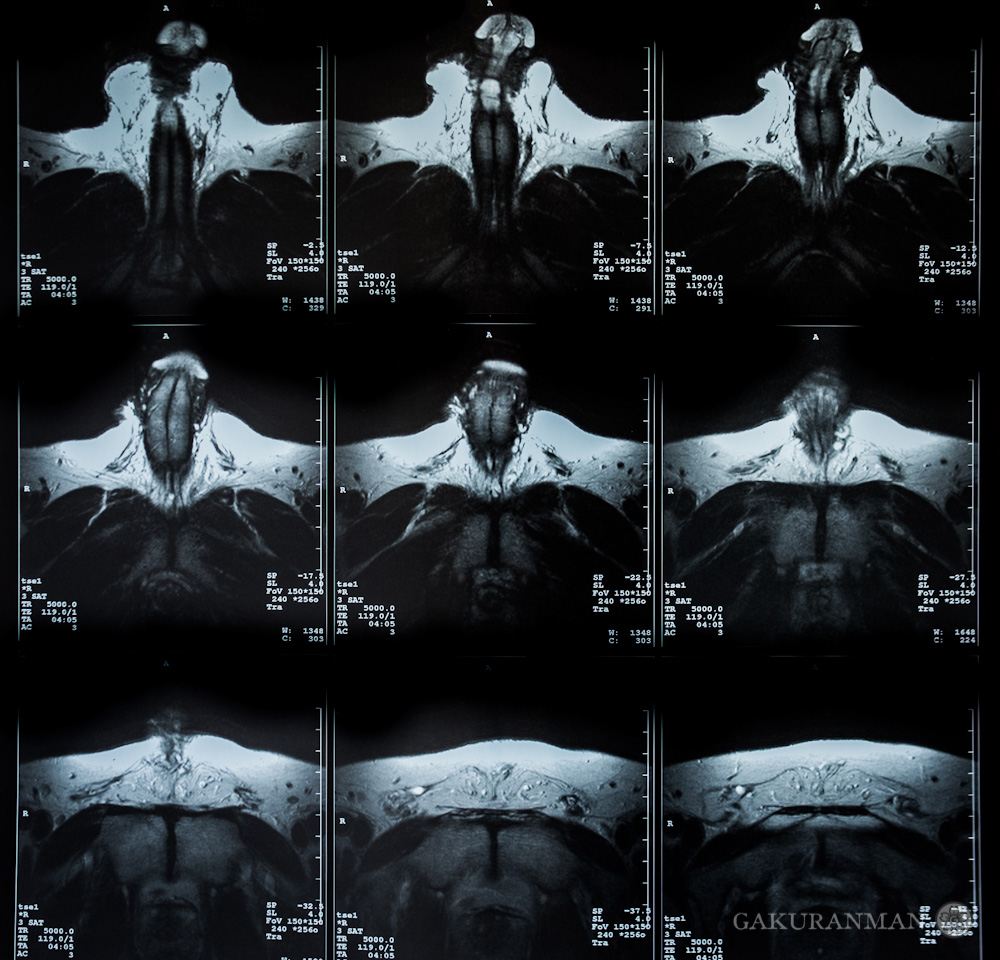

Despite Florian and I being more than impressed with the old hospital and its ageing relics so far, one last point of interest kept us on our toes throughout our exploration. We knew that somewhere hidden inside the old hospital were x-rays and other medical images from patients that had been left behind. Perhaps it’s the eerie look of an x-ray or MRI scan and that we rarely see such images in our everyday lives, or perhaps it’s just that x-ray photographs are a rather more unique find in urbex, but our interest had been piqued and we were determined to seek out some of the old photographs to look at, hoping desperately that the vandals hadn’t stolen them. We needn’t have been worried however, as we soon made our discovery.

Resting quite haphazardly on a box in one of the back rooms were a variety of different medical images – MRI, CT and X-ray photographs – showing the body parts of various patients over the years. Most of the images were actually not of children however, but of adults, likely taken at another hospital.

As you might expect, a majority of the x-rays were of chests, evidently looking for telltale signs of a tuberculosis infection. But a few unique images showed hands and feet, skulls and even the more intimate parts of the human body, such as MRI scans of the brain and pelvic region. My guess is that the scan below was a check for testicular cancer.

It also seems as though employees at the hospital submitted research to journals. With a little bit of searching, I was able to dig up research documents from 1981 referencing tests done at the hospital for hemolytic streptococcus (a type of bacteria that breaks down red blood cells) in elementary to middle-school-aged children between January 1978 and December 1979.

Trying to photograph x-ray sheets proved quite the challenge! Light doesn’t behave well, and it was very difficult to get a uniform spread over the image. It turned out, after messing around for an hour trying different things involving windows and careful setups, that just hand holding an x-ray up to a strong light source worked best to keep shutter speeds high and capture a bright image. There were some truly startling ones too, once I got the technique right!

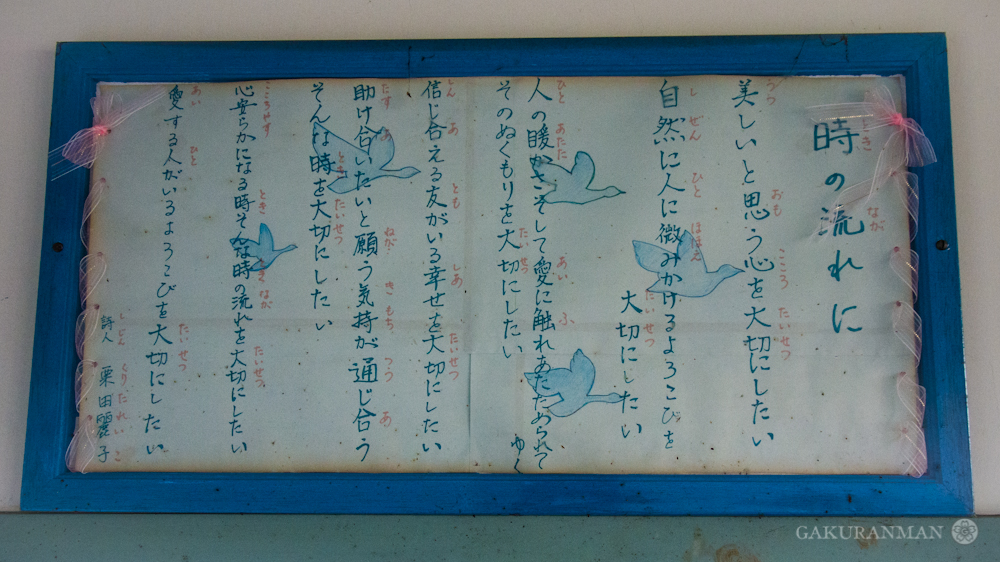

Towards the end of our visit, Florian and I briefly ventured into the ward that had been annexed onto the hospital with the introduction of the school facilities. Most of the rooms were empty now with many of the wooden floors slowly rotting away, but rather bizarrely some rooms were filled with rows of bare metal shelving cabinets. But in the Tsukushi dormitory signs of the old school remained, with a communal bathing area and reception desk near the entrance. Above it was a blue-framed poem (shown further above), rather touching considering the present state of the haikyo sanatorium. I’ve translated it below, with a little bit of artistic licence.

時の流れに

The Passing of Time美しいと思う心を大切にしたい

I wish to treasure a beautiful heart自然に人に微みかけるよろこびを大切にしたい

The happiness of smiling at people.人の暖かさそして愛に触れあたためられてゆくそのぬくもりを大切にしたい

To treasure the warmth from the love of others信じ合える友がいる幸せを大切にしたい

The happiness from trusting friends.助け合いたいと願う気持が通じ合うそんな時を大切にしたい

I wish to treasure those understandings, the times we help each other.心安らかになる時そんな時の流れを大切にしたい

I wish to treasure those times at peace, the gentle passing of time.愛する人がいるよろこびを大切にしたい

I wish to treasure this happiness, found in the ones I love.詩人 栗田麗子

Poet: Reiko Kurita

That just about brings this urban exploration to a close. A truly amazing place, if not perhaps for the location or architecture, but the history behind the building and the medical supplies left abandoned inside. It seems like back in its day it would have been a good place for children to recover and continue to attend school. The opposition from parents and teachers alike towards the closing of the school are surely testament to that. But, as the title of the poem so aptly put it, time passes, and we should treasure those fleeting moments that will eventually come to an end. Let this article record a little of what the hospital once was.

Until the next adventure.

That place has to be haunted for sure!

Wow, I stumbled onto your site while looking up Yaki Imo (your post on the Yaki Imo man was sweet, and I have to say I am so totally blown away and absolutely fascinated by all the things you post – marine bioluminescence, old ruins, cool Japanese stuff. This hospital post is awesomely eerie. So yes, I’m gonna be reading everything and then some. Oh, love your videos too – your “Te-Form” song is stuck in my head now. Thanks, Gakuranman!

P.S. Through your Youtube videos I saw Gimmeabreakman. I never knew all this while the person behind MaggieSensei was a dude! I kept thinking only a woman could post such meticulous stuff and so many doggy pics! lol Well, Victor is hilarious too.

Hi, thanks for dropping by and saying hello :).

I love writing about all this stuff too! I only wish I had more time in the day to do it.

Gimmeabreakman’s dog is indeed Maggie, but from what I understand MaggieSensei.com is mostly written by a female friend of Victor’s :).

Haha, OK, that explains the meticulous detail and all that pink that’s on MaggieSensei.com!

But yes, do keep writing all this wonderful stuff. Japan is absolutely fascinating.

God, I love your photos of ruins!

It’s almost 2am, so excuse me if you’ve written that somewhere, but I couldn’t find it, where in Japan is that?

Cheers! The location has been withheld because very often when these sorts of places become popular, they end up being vandalised.

Fantastic article, Michael! It was a great pleasure introducing you to the place and exploring the inside with you. Like you said: Until the next adventure.

(You should do more lightpainting – I’m sure you would be amazing at setting up photos like that!)

Cheers dude. Fun times as always! I felt my shots this time were not as strong as on previous explorations, but i’m beginning to realise I feel this way every time I go through a set in processing. As predicted, a good chunk the x-ray shots were less-than satisfactory (reflections, focus plane, lack of light) once I got home to check them properly, but the numbers game worked and I got enough usable ones. I hadn’t intended to write so much about tuberculosis itself, but as is the way with haikyo research, one thing leads to another and before I knew it the early morning birds were chirping. Certainly a fascinating place.

I mentioned it before and I’ll stick with it for all eternity – your post-production skills are amazing! I’ve been there with you… Hardly anything looked as good as on the photos. It was a trashed place for most of it, but you managed to arrange the leftovers and shot them right. Really well done, buddy!

Cheers :). It wasn’t always this way though. Flick back through to my earliest haikyo postings and you’ll see quite a difference. I updated the article with a little more information, spelling corrections and a translation of the nice poem. Looking forward to reading your account of the explore!

That is indeed a lovely poem!

I’ve been rather busy recently with urgent matters, but I can’t wait to sit down to write my account of the explore.

Nice find bro!

Thanks!

The silver thing you found is a portable handwarmer, and is still sold today. By this point, the white powder inside is probably just a residue of either the fuel or the chemical process that would have converted it to heat.

Cheers for the information. I’ll update the article with your find :).