Aristotle’s Nicomachean ethics focus on the virtues (aretê) or ‘excellences of character’ and as such he is known as a virtue theorist. He emphasises the importance of ethics as a practical discipline rather than a theoretical one and as such he is interested in finding out the things we need to live well and how we might cultivate the right virtues in order to have a happy and ‘flourishing’ life.

Aristotle’s Nicomachean ethics focus on the virtues (aretê) or ‘excellences of character’ and as such he is known as a virtue theorist. He emphasises the importance of ethics as a practical discipline rather than a theoretical one and as such he is interested in finding out the things we need to live well and how we might cultivate the right virtues in order to have a happy and ‘flourishing’ life.

This ‘flourishing’ or happiness is known as eudaimonia. Aristotle thinks it of great importance to raise people so that they gain the right skills and are able to use reason effectively to discover how best to act in any given situation. In other words, one cannot acquire practical wisdom and understand virtues by purely studying them, one must actually learn by practising virtuous actions. It’s rather like trying to learn social skills just by reading lots of books. One may know all there is to know about how to act in a given situation, but very few people will gain a real understanding of how to socialise well until they put themselves into the situation and actually learn by experience.

Virtues, according to Aristotle, can be divided into virtues of character such as: generosity, honesty, justice, temperance, courage, and virtues of intellect: wisdom, understanding. In order to become a ‘good’ person and attain eudaimonia, one must be a virtuous person by exercising the virtues.

What is the ‘good’?

We need to first think about what we mean by the ‘good’ for human beings and, more specifically for Aristotle, the ‘highest good‘. Aristotle thinks that everything we do seeks some good (which some have argued is a Quantifier Shift Fallacy – detailed later). When we perform some action or do some craft, make friends, eat healthily or experience pleasure, most would agree that we do so because they are in some way good. But the difficultly is deciding how to order the long list of possible things that we think of as good.

This is the search for the ‘highest good’ which Aristotle thinks everyone will agree is ‘eudaimonia’ – that flourishing or ‘happiness’. Living and doing well is being happy. But there is disagreement about what happiness is. To further elaborate on this, consider being healthy and having lots of money. No-one tries to live well for the sake of having lots of money, they desire lots of money because it promotes their well-being – in other words, it promotes their happiness. Similarly with health; people desire to be healthy, but this is a subordinate goal to being happy. Living in good health is one of the many things which allows us to lead a happy life.

It might more easily be thought of as a way of avoiding infinite regress. We perform action A in order to attain goal B. Goal B helps us to attain goal C and so on, until we have an end. Not many people would like to admit there is no ultimate goal or end for us to attain, so for the most part, we desire and end to stop at. This would be the highest good – eudaimonia or ‘happiness’.

Aristotle tries to define happiness by imposing two constraints on it: the Completeness Condition and the Self-Sufficiency Condition. The two principles intertwine and seem dependent on one-other.

The Completeness Condition: An end pursued in its own right is more complete than an end pursued for something else – it is valuable for its own sake. This is as explained above to avoid infinite regress – money, for example, would not meet this condition because it is not pursued in its own right. We desire money for another end, namely ‘happiness’.

The Self-Sufficiency Condition: Something is self-sufficient when it makes life fulfilling all by itself. Again, consider money. Money all by itself would not make for a rich and fulfilling life – we could add other things that would enrich it. But with happiness, this is apparently not so. Happiness all by itself seems to make a life rich and fulfilling. Different things will add together to make happiness, for sure, but we can imagine that amongst many things – wealth, health, wisdom, friends, love, happiness – if we were to choose happiness it would be sufficient all by itself to lead us to have a fulfilling life.

However, it is debatable as to whether or not we live for the pursuit of happiness.

Quantifier Shift Fallacy

Aristotle is sometimes called guilty of making what is known as the Quantifier Shift Fallacy (QSF). Basically:

For every A, there is a B, such that C. Therefore, there is a B, such that for every A, C. (from Wikipedia)

Take a couple of examples:

(1) For every (person), there is a (time), such that they (wake up). Therefore, there is a (time) that every (person) (wakes up).

But this is not right. There is no single time where every person wakes up! Still confused?

(2) For every (person), there is a (woman) that is their (mother). Therefore, there is a (woman) that for every (person), is their (mother).

The English is a little strange as I made it fit the structure of the formula to make it easier to see. But there is clearly no one woman that is the mother of every person! (unless we think of Eve as our mother in addition to the woman that gave birth to us).

So compare it to Aristotle’s statement:

“Every craft and line of inquiry, and likewise every action and decision, seems to seek some good; that is why some people were right to describe the good as what everything seeks.” (NE 1.1)

This could be written as:

(3) For every (activity), there is some (good) for which it (aims). Therefore, there is some (good) to which every (activity) (aims).

But as the two examples above, there is not necessarily a single good which every activity aims for! But perhaps thinking about Aristotle’s claim like this may help:

(3b) For every (activity), there is some (good) for which it (aims). Therefore, there is some (property – namely being good) to which every (activity) (aims).

So, when we say ‘some good’, we are actually talking about a special property which we call ‘good’. So when we perform an action, we actually aim towards a property of goodness (i.e eudaimonia) which encompasses lots of different possible interpretations of ‘good’, not a single thing which is good. This is perhaps why it is dangerous to label eudaimonia simply as ‘happiness’, because it encourages us to think that every action we perform is in pursuit of happiness, but eudaimonia has a deeper meaning than that. Eudaimonia expresses a more abstract ‘flourishing’ of one’s life.

However, a response to this claim about every action leading to some good is made when we consider self-destructive, sadistic or weak behaviour. Surely suicide does not lead to a flourishing life? Aristotle may ignore these types of people, as they are not ‘healthy’ or living as rational agents would do. More later.

Function Argument

So we move on to the Function Argument (ergon argument). Aristotle has said that people live to be eudaimon – to flourish and do well. But how can we do this? What good(s) does eudaimonia or ‘happiness’ consist in? Aristotle says that when a human being, as with other living things and objects, fulfils its ergon, it will flourish and do well.

The function of an eye, for example, is to look. A carpenter, in his work to carve and sculpt objects. In a knife, to cut. These objects flourish when they fulfil their function. So a knife ‘flourishes’ when it cuts, and cuts well. An eye, when it sees and sees clearly. A carpenter when she works hard and crafts objects skilfully.

The same is true for a human being, argues Aristotle. But what is the function of a human being? It has to be something that differentiates us from the animals and other living things, so things like nutrition, growth, sense perception and merely living is not enough. Our function has to be something particular to us. What do we have that animals do not? Reason – Aristotle says the rational part of the soul.

Aristotle found the soul to have different parts. For example, the Nutritive Soul, responsible for growth and reproduction, is found in plants, animals and humans. The Locomotive and Perceptive Soul, for sense perception and locomotion, is only found in found in animals and humans. Then finally, the Rational Soul is found in humans alone. So for a human beings to flourish, is for them to utilise the rational part of their soul. This is done in thinking (using reason), but it must be done over a lifetime in order to bring about a full and complete life (using reason and being virtuous just for one day is not enough). Furthermore, in order to do something well requires virtue or excellence, so to live well must be in accordance with virtue.

“Living well…consists in those lifelong activities that actualize the virtues of the rational part of the soul.” (Stanford encyclopedia of Philosophy)

But how does one go about ‘living in accordance with virtue’?

Developing the virtues

As mentioned earlier, Aristotle distinguishes between two kinds of virtue. Virtues of character, such as temperance, courage, justice, result from habit, and Virtues of intellect, such as wisdom, understanding, prudence, result from teaching. Virtues of character are those that belong to the part of the soul that cannot reason but can nevertheless follow reason. Virtues of Intellect belong to the part of the soul that can reason. Virtues of intellect can then further be divided into theoretical reasoning and practical thinking.

The Virtues of character are gained by habit, and as it suggests, one must perform the actions so that they become natural responses to situations. When we are children, we learn by watching others and by being placed in situations ourselves that require appropriate actions and responses. This is where we start to pick up the correct habits.

Then, as our reasoning ability develops, we become able to think for ourselves. This is the start of our practical wisdom (phronêsis). When combined with our habitual responses, it leads to one being ethically virtuous. We don’t rely on others for help in our decision making anymore and as our reasoning skills develop, so do our emotional responses to situations. We must make decisions by ourself and firmly – virtuous actions cannot be done by accident. Thus, a fully developed adult who reasons well and has developed the correct habitual responses to a wide variety of situations is capable of being ethically virtuous and, moreover, takes pleasure in exercising this honed skill.Taking pleasure in our virtuous actions is again reinforcing the value of performing such actions and, over time, will ensure it becomes habit.

This is not to say that an action is made virtuous by its being pleasurable. A virtuous action will be experienced as pleasurable and likewise, a non-virtuous action be experienced as pain by a virtuous person. It is still necessary to learn about which sort of actions are virtuous and thus promote eudaimonia as children. Actions which bring about pain are likely not to be virtuous. However, this is not to say that virtuous actions are easy and free from pain. Certainly at first, when learning about the world and in extreme situations we will likely feel pressured by the conflict between our desires and our reason. Aristotle himself says that:

“Further, pleasure grows up with us all from infancy on…We estimate our actions [as well as feelings] – some of us more, some of us less – by pleasure and pain. For this reason, our whole discussion must be about these; for good or bad enjoyment or pain is very important for our actions.” (NE 2.3)

So what might we say about all those bad actions, our desires to clearly take the morally wrong path and follow our selfish emotions? Or even of situations that are less-than-clear? Aristotle distinguishes four categories of people:

* Virtuous – those that truly enjoy doing what is right and do so without moral dilemma

* Continent (enkratês = mastery) – do the virtuous thing most of the time, but they must overcome conflict in order to do so

* Incontinent (akratês = lack of mastery) – faces the same moral conflict, but they usually do not prevail to do the virtuous action

* Vicious (kakos, phaulos) – see little value in the virtues and don’t attempt to be virtuous

In each of the latter 3 categories there exists a disharmony. The last category of people Aristotle thinks are driven by their desire for luxury and pleasure and as such are left empty and full of self-hatred. The continent and incontinent people face conflict between their reason and their less rational desires. The desire for pleasure, or wealth for example, are so strong that they eclipse the desire to act ethically. A reason for this is perhaps that we have not developed the proper habits as children and therefore our emotional responses and ability to think intelligently are weakened. But even the most virtuous of people are unlikely to be ‘virtuous’ all the time and slip into the continent category. Such is the nature of selfish desires that we need a system of law and order.

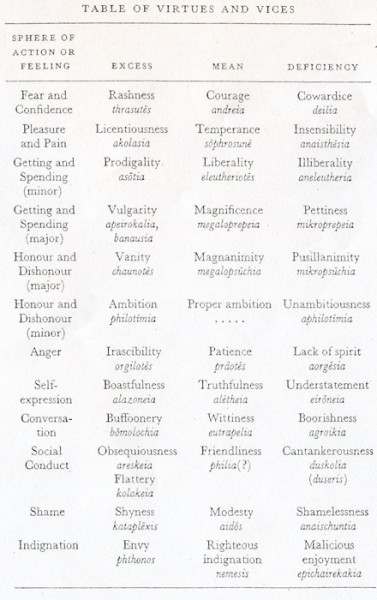

The Golden Mean

What is a virtue? Aristotle says that it is a state (hexis); one that is between an excess and deficiency. This is the doctrine of the mean or the ‘golden mean’:

“Virtue, then, is a state that decides, consisting in a mean, the mean relative to us, which is defined by reference to reason, that is to say, to the reason by reference to which the prudent person would define it. It is a mean between two vices, one of excess and one of deficiency.” (NE 2.6)

So virtue is a state (of character or disposition). It is not a feeling, nor is it a capacity because feelings and capacities cannot be the objects of praise and blame. What Aristotle seems to be getting at here is that, for something to be virtuous is to have a particular feeling (like desire, anger, pleasure, pity) at the right time, in the right place directed towards the right end and right person and in the right manner. It sounds very complicated, but one can only suppose that such conditions will, more often than not, be set automatically because of the correct habits we acquire when growing up.

The mean Aristotle speaks of is the disposition to act and feel in a certain way that lies midway between having an excessive amount of some feeling and a deficient amount of some feeling. This must take into account the situation and circumstances (making it ‘relative to us’), but does not mean that it is whatever we want it to be. The mean is what a wise person would judge it to be. This has the obvious traditional problems of finding the ideal wise person to judge things and teach us in the first place. But it is important to note that all these conditions reinforce Aristotle’s thought that ethics has to be practical – one cannot understand all this in theory alone; one must act out and learn through practice in order to become habituated towards ethics. If Aristotle gave us a set of rules, like many other ethical theories do, there would be no need to become virtuous through practice.

Take a look at the chart below for some examples of excess, deficiency and the mean. Note that, because circumstances and situations are relative to us, the mean does not always lie midway between the two end points. Hence the need for rational thinking and habituation in the person facing each situation. (For example, fear is not bad, but too much fear leads to cowardice and two little fear leads to rashness. In a particular situation, it may be more prudent to run away than to stay and fight with little chance of winning, hence the ‘middle point’ would be closer to cowardice in this situation).

Three lives

Aristotle compares three different lifestyles which help give us a broader picture of the kind of alternatives we have and to further clarify some of the finer points in his moral philosophy. The first life is devoted to pleasure. Aristotle concedes that physical pleasures, leisure and amusements are very desirable in our life as everyone needs relaxation. However, he says that such pleasures play a lesser role than other ‘higher pleasures’, because we seek amusement and relaxation only to return to more important things. Therefore physical pleasures cannot be our ultimate goal.

The second life he assesses is devoted to politics – a person exercising justice and promoting the good of a city. This life is better than the first simply devoted to pleasure because the person utilises practical wisdom and virtues such as courage in the face of a war or generosity towards the people of the city they govern. But Aristotle holds that such a life is still lacking because the person must exercise these virtues for the most part in response to situations when they have gone wrong. Furthermore, it is in conflict with what Aristotle holds to be the highest pleasure, that is theoria, or ‘theoretical contemplation’.

Thus we come to the third life, the life of the philosopher, who devotes himself to continuous contemplation. He has already achieved a theoretical wisdom, has a basic understanding of the universe and the things needed for living an uninterrupted life (such as food, shelter – etc) and so can devote himself to contemplation in the manner of a god. Aristotle likens the philosopher to a god and says that god thinks endlessly using reason. So by human beings using their reason in the fullest sense, to contemplate and do philosophical activity (which the politician does not – or even if they do, they cannot devote themselves it it), they can come as close as possible to the gods.

This focussing on theoria seems to undermine the practical virtues we have seen Aristotle speaking of earlier. If the paramount activity is to do as a philosopher does and contemplate, what use do the practical virtues have? Aristotle might reply that even a philosopher will need to figure out the means in different situations. Also, the normal problems of leading a virtuous life still exist, so there is still the need to develop practical wisdom and the ethical virtues in order to be able to respond to ethical dilemmas and other such situations.

But what of those individuals who choose to live a political life for the good of the city and other people as opposed to the seemingly selfish one of the philosopher? Aren’t they to be commended for choosing what Aristotle considers the ‘second-best life’? What’s more, saying that the gods reason and think undermines our earlier argument that a human being’s particular function is reason. How is it unique to us if we share it with the gods? With these things in mind, let us move on to consider challenges to Aristotle.

Problems for Aristotle

Let’s begin with some problems that have been directed at Aristotle’s function argument. Aristotle seemingly makes the jump from pointing out that individual object shave functions, such as knives, eyes and even carpenters, but that does not mean that human beings themselves have to have a function.There is an extrapolation form part to whole.

As mentioned, the Gods use pure reason, but human beings are hybrids between gods and animals because they are both godlike (rational) characteristics and animal (biological) characteristics. Similarly, Nagel’s bottle-opener-corkscrew argument challenges Aristotle’s argument that every thing has a unique function. What is the unique, particular function of a special tool that consists of both bottle-opening and corkscrewing capabilities? It seems that such an object would have no special feature and thus no ergon at all. Indeed, it even raises the question as to why we couldn’t consider that there could be combined erga and that there could be objects with more than one function.

In his article, Nagel further considers that faculties such as reason and the act of contemplation are, while indeed qualities which distinguish us from animals and plants, still subservient to lower functions. If our metabolic system and other bodily functions did not work as they do, we would not be able to reason correctly and thus not be able to flourish. But no matter much the lower functions provide a setting and are under the control of reason, the dominant characterisation of a human being is still in his reason as it allows the individual to completely transcend other worldly concerns. Nagel says that this is what tempts Aristotle to think that the supreme good for human beings is realised in being intellectual because the “purest employment of reason has nothing to do with daily life” (Rorty, 1980. p12). We can ‘live’ biologically as the animals do with our bodily functions supporting our ability to think and even having practical reason provide order to our lives, but the real difference and essential nature of human beings is in their ability to use reason to transcend themselves and become like gods. It is in this capacity that we are capable of eudaimonia whereas the animals are not (p13).

Another of Aristotle’s problematic areas is where he talks about people who lack wealth, power or good looks. It seems that people who develop the correct ethical habits and reason effectively should live a morally virtuous and life in accordance with eudaimonia. But actually, Aristotle says, the lack of such basic things like money, friends and good looks are likely to cause the person to have a less-than fulfilling life when compared to a virtuous counterpart who does have these things. The opportunities for virtuous activity will diminish and, over a longer period of time, a person who lacks such goods will lead a less flourishing life. This seems a rather unfair state of affairs, but fits in with common sense and reality. It seems that good fortune is also necessary for a complete and fulfilled life.

The theory of the mean is also open to objections. One might consider a situation where one must decide between visiting a sick friend or keeping an important promise. Here, the doctrine of the mean does not seem to help us decide which action to take or which is the more virtuous. Aristotle’s idea of the mean between and excess and deficiency seems inapplicable in some situations. But we might reply to this by saying that we do aim at a mean after all. In deciding whether to visit our sick friend or keep an important prior engagement, we must demonstrate the right degree of concern for both situations. We search for the answer by being neither too sympathetic for our sick friend’s cause nor too thick-headed to keep a promise at the expense of the immediate need to see our sick friend.

Isn’t Aristotle’s theory biased towards the life of intellectuals and, in particular, philosophers? Why should the best kind of life be one filled with contemplation when there are people working hard as political leaders to bring happiness to a wider community? What’s more, why can’t people be fulfilled and happy to the fullest extent by passionately leading the life most suited to them? A farmer may not philosophise, but he knows his trade and cares for the animals. He grows crops, sells some to others for food or materials and uses the money to lead a humble but satisfying life with his family. It seems insulting to say that such a man is less happy than a philosopher who spends as much of his time as possible in contemplation about the greater meanings of the world. Indeed, some would even say that thinking about such deep issues, especially about what it means to be ‘happy’, actually decreases the amount of happiness one feels!

**********

Sources: Lecture handouts written by my lecturer Dr. Gerald Lang, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ‘Essays on Aristotle’s Ethics’ (1980) by Amelie Oksenberg Rorty and ‘Classics of Moral and Political Philosophy’ (2005) by Michael Morgan

What does inquiry mean? As used by Aristotle.

Great writeup, helps me understand Aristotle

Great writeup, helps me understand Aristotle