T’was the brink of winter in mainland Japan when haikyo buddy Florian and I decided to venture north. Our joint adventures in urban exploration had not taken us much above central Japan until now, but we both felt it was time to step foot in largely unexplored terrain. To go to that most sizeable island crowning Japan’s archipelago, Hokkaido. Snow Country. And indeed it was!

The cold winter air whooshed its way through the gaps in the boarding platform and deep inside my loose-fitting clothes as I disembarked my plane in Chitose. While mainland Japan might still have had the pleasure of a few remaining autumn reds and yellows, Hokkaido was already comfortably into its winter boots. Not that I had thought to bring any myself, mind you. It’s just Hokkaido in November, right..? I thought.

But by the time I had reached central Sapporo, I could already feel the ice on the air. Florian was cozied up in his room at the Toyoko Inn awaiting my arrival. Our scheduling meant that he’d arrived Thursday morning, having taken a day off work, and me – I’d rushed out at 6pm to catch my flight from Haneda. After a quick check-in and reunion, we both hit the sack ready for the first of our 4-day expedition.

This is explore #1 of Haikyo Adventures in Snow Country, baby! See the post for the full list.

Snow Country

After grabbing the rental car from a nearby Mazda branch, we diligently programmed the car-navigation system and set off to our first location for the day – Horonai coal mine (幌内炭坑) and the accompanying substation (変電所). Florian had done a lot of the work collecting potential locations, and brought along a stack of printouts showing our destinations. He’d also included a sizeable number of backups – you never quite know what you will find when you arrive at haikyo. Sometimes the places will be guarded or inaccessible. Other times perhaps badly damaged or too dangerous to enter. Sometimes they don’t even exist anymore! But Florian had assured me Horonai was still around, and being a bit of a fanatic about abandoned mines, he was eager to get out there and take in the greying concrete structures. Me – I was just excited at the thought of haikyo in the snow!

On the way to the mine, we chatted about urbex and haikyo, recounting our trip to Okinawa in the summer, regaling each other with tales of friends and follies, and also possible future expeditions. Having somebody else in the car to exchange banter with makes for a much more pleasant driving experience, I found. Before getting my Japanese driver’s licence the previous spring, I’d always thought the driver must get pretty tired, but surprisingly I found this not to be the case. Before we knew it, the asphalt had turned to ice and we’d hit the end of the road. Before us lay the beginning of a snowed-in track that concealed the majestic red brick substation.

But we weren’t alone out here. Rather impressively, an older Japanese fellow emerged from the snow, a frisky dog pattering by his side. Usually this wouldn’t have even made me look twice, except for the item our friend clasped in his hand. Nothing other than a rifle! Japan has exceedingly strict gun laws, and regular citizens can only own two types of weapons – a shotgun or a rifle. Both require that the holder keep an updated licence and undergo various strict tests to make sure that they are competent in using the gun. As such, the sight of a gun-toting granddad was quite the surprise. Suddenly we really were in Hokkaido’s backcountry. Dogs. Deer. Bears. All were potential encounters. Perhaps we may even find the remains of a fresh kill? I gave him a friendly nod as he drove off to warm up back at home, giving us the opportunity to gather our kit and set off down the snowy road.

Fortunately for us, a set of wide tyre tracks had been left imprinted in the snow, allowing us to walk the kilometre down the road to the substation without trudging through such deep snow. Even with this advantage however, it wasn’t long before my trouser legs were damp and Florian was regretting wearing jeans. Neither of us had brought wellingtons with us. Not that we would have had much luck finding a size to fit our absurdly large foreign feet in Japan anyway, mind.

Red and White

Breathing in the fresh, crisp air, I was energised! Eager to trudge around and get wet for a few photographs. Pointing downwards to a few concrete buildings, I tried to persuade Florian to head over to them. But as much as I tried he kept pushing us on to the end of the track. A good thing too, in retrospect. The snow was deep and without a lot of care and patience, it would be rather difficult to make our way safely down to the relics.

Most of the buildings associated with the mine had long since been demolished due to safety concerns, but a few choice structures remained, dotting the snowy landscape and poking their grey skulls out of embankments. The crowing jewel of all of them however, is the remaining transformer substation. A grand red-bricked building that stood in delightful contrast to the shimmering frosty white around us. It appeared to still be used for tourism and properly maintained for its heritage, although I doubted it saw many visitors at this time of year. Locked up with a sizeable padlock it was almost a futile endeavour, but a small opening allowed me to scramble inside, rust covered and grimy, to snatch some photos.

Hokkaido’s Oldest Mine

Although unbeknownst to both Florian and I at the time, Horonai Mine is actually Hokkaido’s oldest large-scale mine, and the accompanying government-managed railway is Hokkaido’s first railroad, built to transport the coal extracted as well as passengers.

The mine, opened in 1879, was something of a pioneer for Japan’s mining industry and remains one of the most important in its history. Interestingly, the Meiji government commissioned several foreign nationals over the course of the mine’s opening to design the railroad transport system. American engineer J.U. Crawford eventually oversaw the construction project and although the railroad failed to be profitable, was an important part of Japan’s steps to industrialisation. The mine was finally closed in 1989, over 100 years later.

While Florian was outside shooting the nearby Horonai Shrine, located on top of a hill in the pouring snow, I slapped my hands together and watched my breath produce clouds of white. Even inside the old transformer substation, the chilly winter air surrounded me. The building was in much better shape than I had imagined, however. A heaven for old machinery and heavy, metal apparatus.

Signs off life were everywhere, from pin boards covered with photos and recent posters advertising memorial events, to a row of wellington boots, ancient mining helmets and a huge lump of Horonai coal. Various other interesting instruments were carefully placed on a bench near a modern heater, and a model of some of the mine’s facilities rested on a large table dominating the centre of the first floor.

I busied myself with taking pictures and then headed up the concrete steps to the second floor of the substation, where the large metal carcass that once controlled the electricity lay resting in peace. I’m always stuck for how to photograph machines with lots of buttons. Do I go in for a closeup? Shoot it wide to show the giant in its entirety and contrast it with the cool white of the windows? There are so many little details that I wish I could simultaneously show for an object.

A small shrine decorated the back wall of the second floor. Beside it was this painting of a horse. Knowing we had a full day’s exploration ahead of us, I didn’t try to make too much of it, but evidently it holds some historical value, being preserved next to the shrine like that.

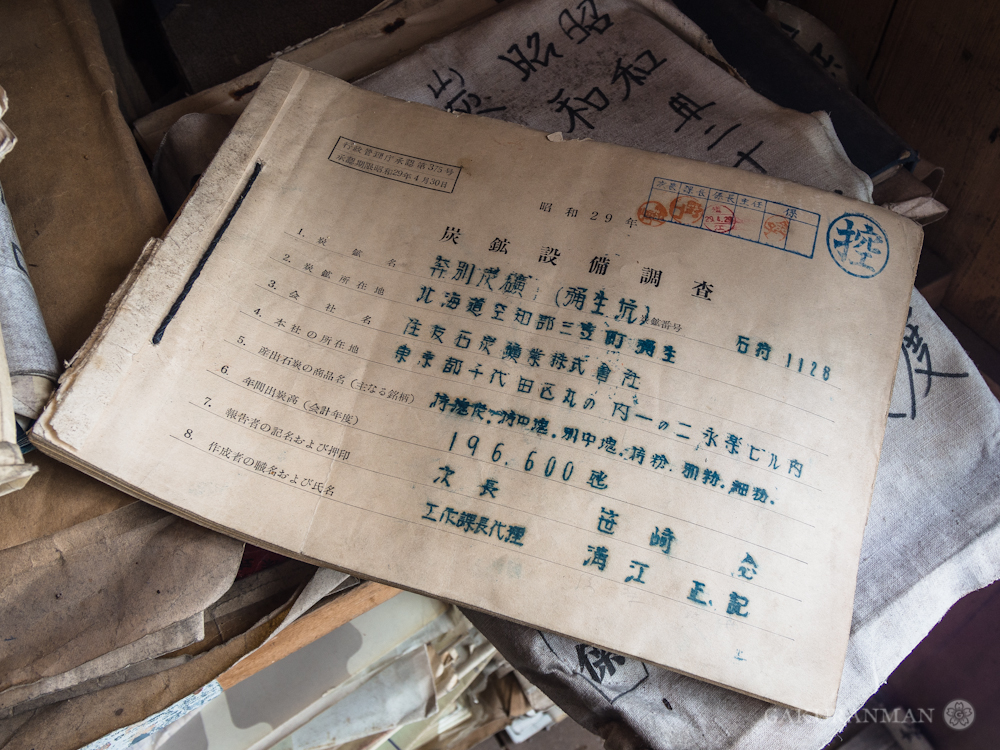

A makeshift office looked out onto the huge vertical windows etched with signs of the cold outside. Over on the far wall was a set of storage units, filled with dozens and dozens of old documents about the mine’s history and transactions. Below is documentation detailing an inspection of the mine’s facilities dated 1954.

Snow Blindness?

Back outside, Florian and I shot some more of the surrounding scenery, including the shrine. I enjoyed re-enacting wizarding duels with an extraordinarily long icicle I snapped off a freezing ledge just in front of the main torii gate. Just because.

Part of what makes this hobby fun and what continues to hold my interest so much definitely has to do with the Peter Pan syndrome. Off exploring the wilderness, sneaking around old buildings, clambouring through deserted tunnels and the like are all things we longed to do as boys. Perhaps for one reason or another we were denied this opportunity, or we just never completely had our fill of it, but now as adults we have the freedom, knowledge and means to pursue these latent desires. We never really grew up at all. Quite simply, its just those these pure, unadulterated childhood feelings of playtime bubbling so effervescently back to the surface that are responsible. It’s no surprise that while exploring, we often feel the urge to goof around and have fun.

And so it was that on the way back to the car, still brimming with excitement from the perfect tranquility of snowy Hokkaido and crusty ruins, that I decided to plop myself down and do a snow angel. Little did I know that this angel would be the start of several minor disasters throughout the trip, fortunately none of which ended too seriously.

Ignoring Florian’s sage warning about hidden rocks and spiky things, I threw myself backwards onto the fresh snow. Splat. A bed of soft whiteness surrounded me and I gleefully swung my arms up and down. Removing my glasses for the photo, I instructed Florian to hurriedly get a few shots of me before we left. After all, the last thing I wanted was to be wet through for the remainder of the day. Florian took the pictures and handed me the camera. Something was amiss however. As I stood up and looked around, I realised that everything was blurry.

Glasses! Florian! — Don’t step a step, I think I may have dro —

*Crunch*

A horrible realisation that I had done exactly what I feared took hold. I picked up my broken spectacles and sighed. The lens hadn’t broken, but part of the metal holding it in place was bent and the wire snapped. There was no way I could wear them for the trip. As the only designated driver, this posed a big problem. Fortunately however, I had a few pairs of contact lenses, just in case. We would be able to continue our haikyo trip for now, but I didn’t have enough lenses to last all 4 days. At some point we were going to have to find a glasses store…

Until then however, we had two more stunning locations to visit. Onwards!

Stay tuned for the next instalment, fellow adventurer!

(Bonus; Read Florian’s account of the exploration here, with more history!)

Mannn, how do these places not get looted? So many great treasures. Shocked that a gorgeous painting like that has simply been forgotten. Note to self, get corrective eye surgery as soon as it’s financially viable :P I couldn’t poke my eye.

I can all too well imagine the horror of stepping on one’s glasses! I’m sure I’ve done the same at one time or another. I even once had a rubber ball hit me in the head so hard, one of my lenses popped right out of my frame.

Anyhow, it’s great to see how you both have kept your sense of humor and fun. These ruins do look pretty clean, but are fascinating nonetheless. Can’t wait to see and read about the others!

Thanks for the comment :). It’s actually the first time it’s happened. Usually I’m pretty careful with my glasses! But yea, keeping a sense of humour is so important. The mishap that came later in the trip was much harder to laugh about though!